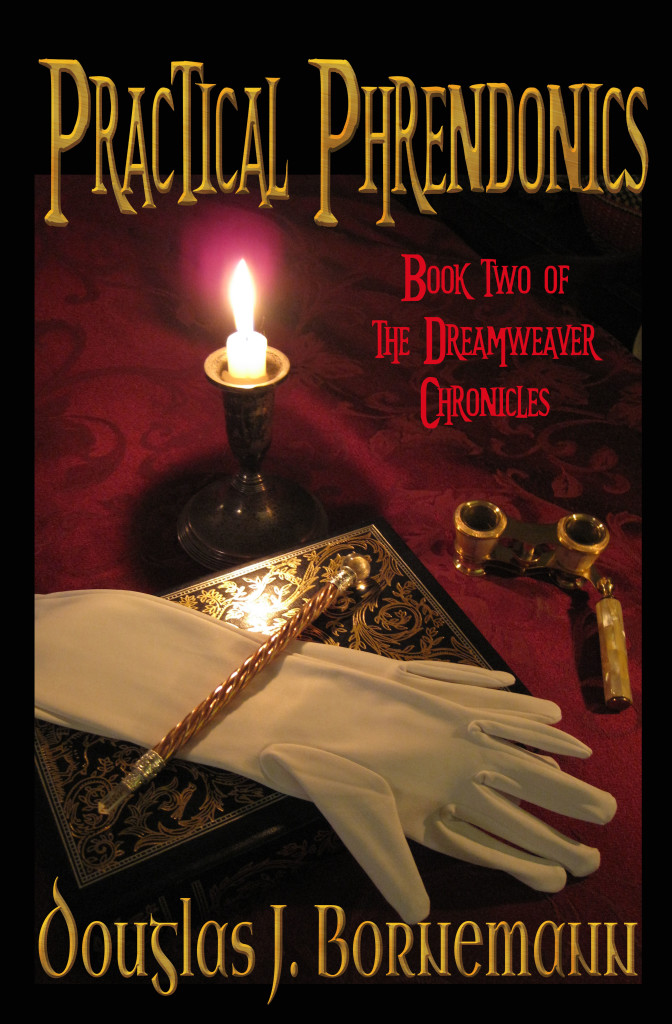

Oh, and, by the way, the ebook version of Practical Phrendonics is currently on sale for 99 cents.

(to which The Demon of Histlewick Downs is a standalone prelude).

Acquiring expertise first requires recognizing the need…

Last year’s publication of Hanged Man’s Gambit, the final book of the Heiromancer Trilogy, was the culmination of over fourteen years of work. When I started, I hadn’t the slightest idea what I was in for. From years of running games, I knew a little something about developing characters and the elements that make a plot meaty and satisfying, but publishing is a different beast. After law school and a Ph.D., I was also under the impression I knew how to write. I didn’t – at least not at the level necessary to publish a professional-level novel. Of all the things I needed to learn, that was far and away the toughest. Writing well requires more than vision. It requires more than talent. It requires more than a basic grasp of grammar. It requires more than being widely read. While all these things are helpful, professional-level novel writing requires expertise.

How does one acquire expertise?

The first and hardest step is recognizing you don’t have it. If you haven’t had some training, you can safely assume that not only do you not have it, you aren’t in a position to evaluate whether you have it. That’s simply the nature of the game and a natural consequence of the Dunning-Kruger effect. All beginning writers go through this. Those who don’t get past it before they publish are responsible for the continuing truth of Sturgeon’s Law. Assuming that since you’ve read novels that you are now qualified to write them is like accepting a job as a master chef because you’ve eaten at a few fancy restaurants. Chefs train for years to master techniques and learn the subtleties of their craft. While you might be a good home cook, if you haven’t trained, you’re not a chef. Mastery of a craft like writing requires an understanding of the prevailing culture, an appreciation for what’s already been done, and a vision for the boundaries you intend to push. You need to know, for example, why certain approaches (like the main character describing herself in the mirror) are verboten; why info-dumps are problematic; why tense scenes require a more staccato delivery; what constitutes overuse (or awkward use) of dialogue tags; what makes for a workable inciting incident; the differences between good grammar and clear, strong prose; how to recognize and eliminate unnecessary repetition; how to identify and eliminate plot-irrelevant details; how dialogue is properly punctuated; and a thousand other things. Only once you understand these rules can you both employ them effectively and know when to productively break them.

The second step is to recognize that to achieve some measure of craft, you’ll need trained guidance. Books on the subject can help, but nothing gets the message across more effectively than feedback on your own work by someone who’s already acquired the requisite expertise. Your mother, even if she’s rigorously honest, might only be able to tell you something’s wrong. Without the appropriate expertise, she likely won’t be able to tell you why elements of your story rub her the wrong way or strike her as amateurish. Your best bet is to find a skilled editor who is willing to both edit your prose and explain the reasons underlying those edits. That, of course, is a huge challenge in its own right. Because you’re now aware of the Dunning-Kruger effect, you’ll realize that since you’re not in a position to evaluate the quality of your own prose, you’re probably even less well positioned to evaluate those edits.

So, how will you be able to evaluate whether the editor you’ve selected has any more expertise than you do? It is a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem. First, recognize that since there’s no regulatory body governing minimal competence for editors, anyone can hang out a shingle and charge you for the service. To complicate things further, some folks claiming to be editors are little more than scammers. Next, recognize that even non-predatory editors may be afflicted by Dunning-Kruger – they may simply not recognize their editorial skills aren’t up to par. My best suggestion is to attend writers’ conferences (such as The Southern California Writers’ Conference). Assemble a cohort of friends who are also trying to acquire writing expertise and get their honest feedback as a way to start acquiring some expertise that you can then use to help you evaluate editorial work. Professional editors also often attend writers’ conferences, and you can get an idea of whether some of these folks’ personalities would be a good fit. Check editorial credentials such as past clients and also check the Preditors and Editors website (once it’s back up and running). And most importantly, when you’re ready – when you feel you can’t possibly make those pages any better – get sample edits (preferably for the same pages) from multiple vetted editors. Many reputable editors will do such sample edits for free. Multiple samples will enable you to compare the editors’ methods and to see how their suggestions affect your prose. Even if you’re choosing from a group of highly capable editors, there’s as much art as science to editing – your artistic styles won’t always mesh.

Also be aware that Dunning-Kruger applies equally those who will review your work. When you publish, you’ll be submitting your book to a broad range of readers. The majority won’t be in a position to meaningfully comment on your level of craft because they simply haven’t acquired the level of expertise that would enable them to evaluate it. You acquire that expertise because it provides readers with a smoother, less-jarring, more-immersive reading experience, not because you expect readers to recognize what a skilled craftsperson you’ve become. That you’ve improved the reader experience will increase the chances for positive reviews, but will not guarantee them. For some, burnt tater tots and TV dinners are the epitome of haute cuisine, and if that’s what they like, reviewing them accordingly isn’t necessarily wrong. That also means if you don’t serve tater tots, those folks simply won’t review you well, regardless of your facility with the foie gras. On the other hand, that smaller fraction of readers who have acquired a measure of writing acumen are likely to expect high-level craft as a matter of course. It therefore won’t occur to them to praise a work for its craftsmanship, but they will be among the first to crucify you should you fail to live up to their exacting craftsmanship standards. Thus, it’s predictably rare for a review to accurately recognize and appreciate hard-earned writerly skills, but when it happens, it’s an occasion to be cherished.

/

(0)Dislikes

(0)Dislikes (0)

(0)